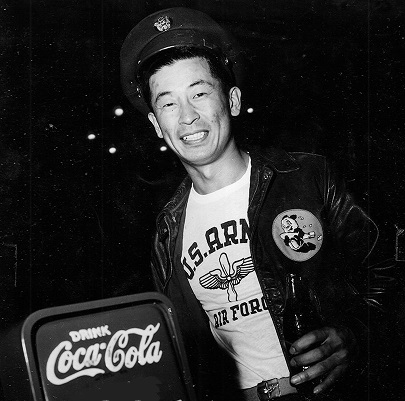

The American airman’s spectacular bombing missions over three continents during WWII earned him a trifecta of Distinguished Flying Crosses and front-page stories. But when the wheels came down, this son of Japanese immigrants faced nonstop racial intolerance, hatred and threats of violence from within his own ranks. Ben Kuroki called it his hardest battle: “I had to fight like hell for the right to fight.”

When Pearl Harbor is hit, the 24-year-old Nebraskan farmer drives 150 miles to a recruiter who is willing to sign him up in the Army Air Corps. After a year of menial tasks, a teary plea to his lieutenant earns him a plane seat. Ben becomes a star turret machine-gunner, thanks to his bird-hunting deadeye and detailed first-aid knowledge.

His run-and-gun raiders begin hammering Hitler – from the “Desert Fox” Rommel’s tanks in Africa, to submarine pens in France, to a daring treetop-level surprise attack on key German oil fields (above).

At one point, they’re forced down and caught. But Ben’s grateful crew assigns him two 24-hour “wing men” until their freedom, then later during liberty time. The pair help take on his bar bigots, hide him from racist cabbies and “No Japs” motel owners, and save his life after a bloody knife attack.

Ben returns on home leave after 30 missions, showing “battle fatigue” signs (PTSD). But when the Pentagon asks the flyer to help with recruitment, he agrees to appear at three Japanese-American internment camps (Below).

Young men love Ben and sign up in droves, but he gets angry receptions and threats of violence from the elders who lost their rights, property and dignity. The experience leaves him “deeply uncomfortable.”

Then sad news from Nebraska: Childhood best friend Gordy Jorgenson, who once saved his life after a hunting accident, was killed by Japanese soldiers. Ben’s rage pushes him to apply to become the first Japanese-American to bomb Tokyo – but the Army says no.

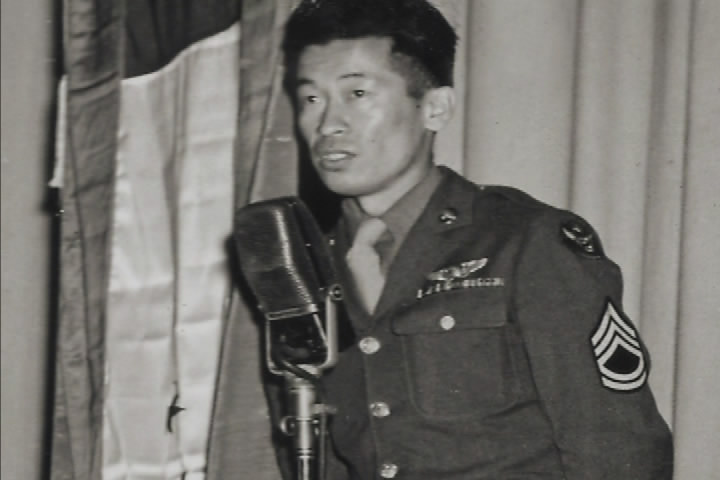

Later he’s invited to speak at San Francisco’s world-famous Commonwealth Club (Below). He begins by greeting the hate-filled faces with “sharp wit and a ready smile.”

Then he delivers a profound message that awakens the nation.

From the 45-minute talk: “I have the face of a Jap, but my heart is American. [My] tunnel-gunner was Jewish, the bombardier a German, the left waist-gunner an Irishman [and] I flew with an American Indian pilot. When in combat, you begin to understand what brotherhood is all about, what equality and tolerance really means. You’re living and proving democracy.”

Ben’s standing ovation lasts 10 minutes. The 1944 speech is put on national radio and even short-waved to Japan. The public pressure sways the War Secretary to allow the hero his exclusive wish to go bomb his parents’ ancestral home – for Gordy.

In honor of Ben, his new crewmembers on a Pacific island-hopping airstrip rename their new B-29 Superfortress (Above).

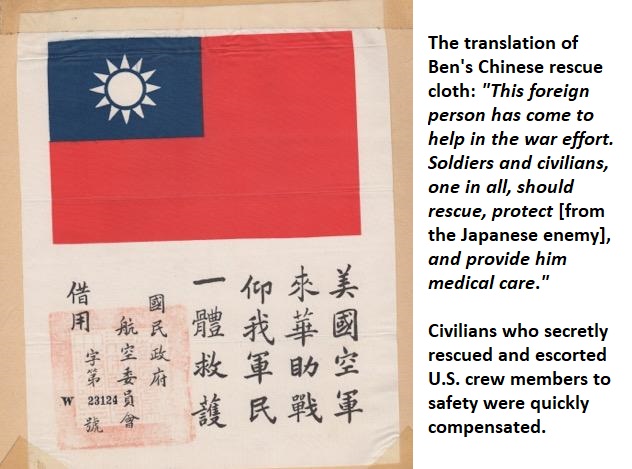

Like the American “Flying Tigers” doing missions nearby with the new Chinese Air Force, Ben is given a “blood chit” rescue cloth, adorned with China’s flag and writing – just in case his bomber has to crash-land on the mainland.

The gunner signs up for an astonishing 30 more missions. But he is stopped at 28 because of another historic Superfortress, parked right next to his – named the “Enola Gay.”

When 28-year-old Ben is discharged from the military in 1946, he begins what he called his 59th mission: giving racial tolerance speeches around the country. While on tour in Utah, he meets a Japanese-American university student named Shige Tanabe. They marry a half-year later and start a family.

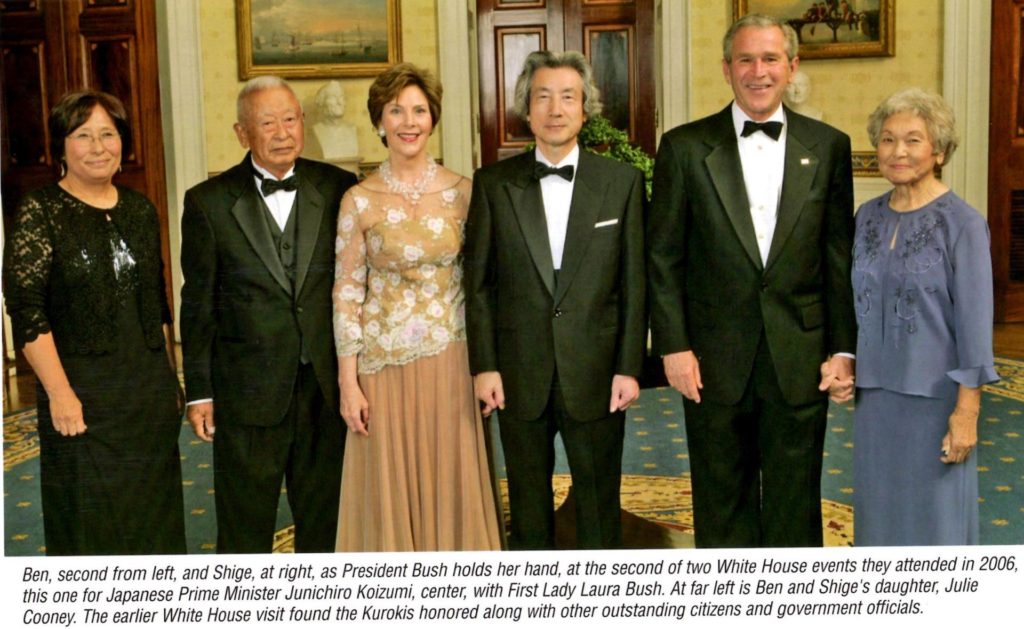

After a long public campaign, the forgotten 78-year-old vet is awarded the U.S. Army Distinguished Service Medal in 2005. The next year, the visiting Japanese Prime Minister asks to meet Ben – which is arranged by the White House. ##